How the pandemic has worsened existing inequalities

It is more important now than ever before for food banks to address systemic inequality

By Emily Gallion, Grant & Metrics Manager/Advocacy Manager, and Caitlyn McIntosh, SNAP/Outreach Lead

There are many positive signs that the hardships of the pandemic are easing. More and more people have been vaccinated. Many businesses have reopened. We are relieved that our lines are much shorter than they were one year ago.

While we are hopeful for the future, we also know that for many households in our line, it will take much longer to rebuild.

At its core, food insecurity is an money issue. Food insecurity is, in many ways, a symptom of other evils, including poverty and generational inequality. While providing a box of food may help a household stretch their income and afford other expenses, such as utility bills and medication, it will not push them into the next income bracket.

The United States is widely considered a wealthy nation. However, that wealth is not shared by all who live within its borders. At the height of the pandemic, Feeding America estimated that over 50 million people were food insecure. At the same time, the top five billionaires saw a 59% increase in their wealth.

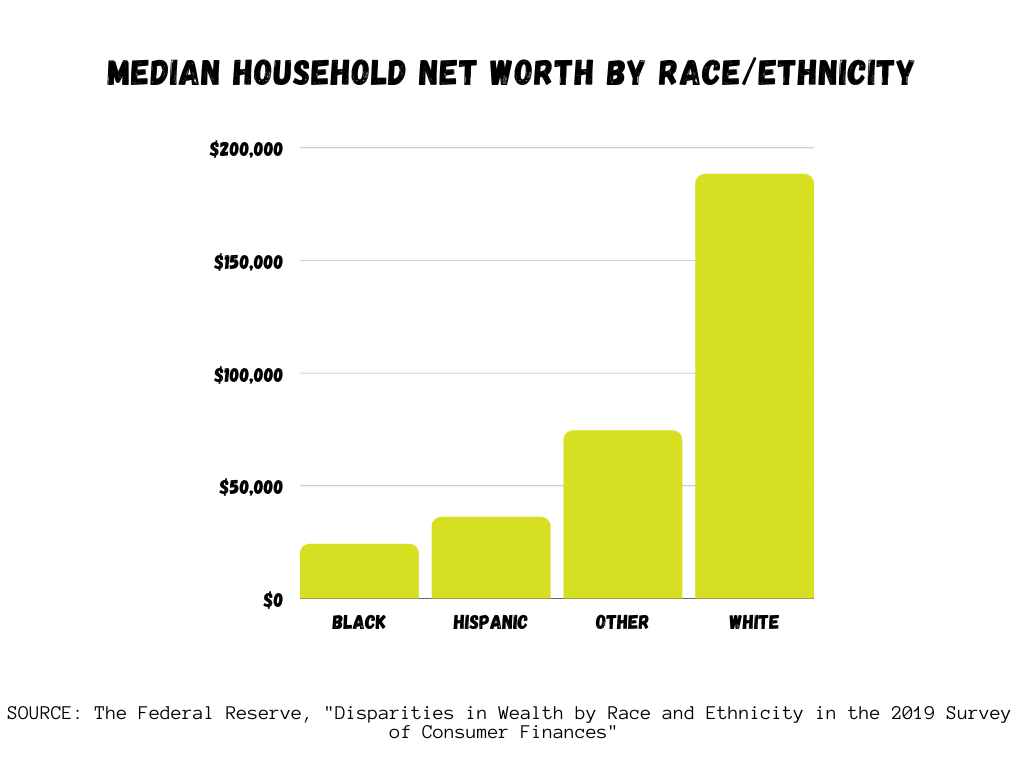

In many ways, the pandemic has reinforced existing inequalities. In figures recently released by the federal reserve, Black households had a median net worth of less than 15 percent that of white households.

Historically, families of color have been subjected to a wide variety of racist policies and practices, such as redlining, discriminatory lending, and mass incarceration, which have made it more difficult to accumulate wealth. Contrary to the “bootstraps” mentality, our nation’s past transgressions continue to have an impact on current generations: Researchers have estimated at least half of all wealth in the United States is transferred via bequests and other gifts.

The economic impacts of the pandemic have been disproportionately borne by low-income households and people of color. On average, households in the United States have actually increased their savings amidst the pandemic.

According to a Harvard-based research study, households with higher incomes reduced their spending by 17%, while low income households only reduced their spending by 4% in the same time period. Additionally, almost 70% of low-wage workers in zipcodes with the highest rent lost their jobs during the additional shutdown.

Given this data, it comes as no surprise that nearly 14% of Americans exhausted their emergency savings during the pandemic. This trend will make households impacted less resilient in future crises.

The disparate impact of the pandemic on US families is reflected in lines at The Foodbank and other food assistance programs. According to the Urban Institute, Black and Hispanic/Latino households were more than three times as likely to access charitable food assistance during the year 2020. The author of the brief wrote that this is “likely reflecting both higher rates of need before the pandemic and the recession’s significant impact on households of color.”

As we have mentioned before, food insecurity can also lead to poor health outcomes and perpetuate the poverty cycle. The high-carb, low-nutrient diet and other dangerous “coping mechanisms,” such as medication underutilization, that are associated with food insecurity can lead to preventable health problems down the road.

Unfortunately, this cycle begins at childhood at no fault of the children. A study by the Alliance to End Hunger found that schools with 90% white children spend $733 more per child than schools with 90% children of color. These dollars affect critical programs like school lunches, where schools that have a high percentage of students of color are half as likely to adopt healthy lunch options as the schools with majority white students.

All of these inequalities are a direct result of the laws, policies, and procedures that have been implemented for decades. There is no shortage of food in the United States, which regularly wastes 30-40% of the food it produces. Because food insecurity is not caused by a lack of food, it cannot be solved long-term by providing food alone.

Policy interventions have had a demonstrated effect on the severity of food insecurity amidst the pandemic. According to The Urban Institute, food insecurity dipped in May after the first stimulus checks were released, dropping from 22 percent to 17.9 percent. Then, rates rebounded to 19.6 percent from May to September. This relationship demonstrates that while relief packages have been effective, the “start and stop” pattern they are released in contributes to related fluctuations in food insecurity.

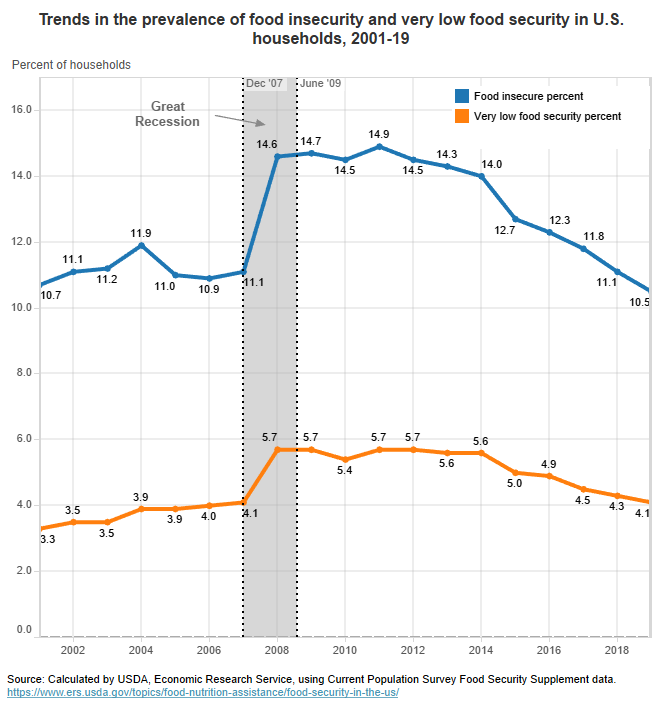

Given the severity of the inequalities present in the economic crisis, it is important now more than ever that food banks and other anti-hunger or anti-poverty organizations advocate for systemic change, partner to address the social determinants of health, and continue to disprove harmful myths about poverty in the United States. We should also be careful to set our expectations for recovery: Many lessons can be taken from the recovery curve of the Great Recession, which lasted about 10 years.

While early signs of economic recovery are positive, we must pay close attention to the data we use to ensure that no group is left out of recovery. We are hopeful that this recovery will be faster than the most recent recession.

The Foodbank takes part in a variety of activities to address the root causes of hunger. While food assistance plays an invaluable role in ensuring that “no one should go hungry,” the long-term issue of food insecurity cannot be solved with food alone. For more information about our work, we invite you to read the following previous blog posts:

● SNAP is critical to our hunger relief work – here’s why

● Shortening the line: why we hire re-entry

No comment yet, add your voice below!