The Social Determinants of Health: Connecting the dots between race, health equity, and the food landscape

How racial differences in food access contribute to poorer health outcomes for communities of color

By: Caitlyn McIntosh, Development Manager and Emily Gallion, Grant & Advocacy Manager

You may have seen headlines recently that Black communities are bearing the brunt of the COVID-19 crisis. Nationally, Black individuals account for about double the proportion of the COVID-19 death toll as the portion of the overall population they represent.

Some public health officials have received criticism for suggesting that the correlation is primarily due to higher rates of obesity and other chronic diseases among the Black community. However, the relationship between chronic diseases, race, poverty, and food insecurity is much more complicated, and it has everything to do with the social determinants of health.

While “social determinants of health” may seem to be a relatively new term in the public health space, it was used as early as 2004 by the World Health Organization (WHO), which defines it as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.”

The United States Center for Disease Control (CDC) has also recognized the social determinants of health, defining it as “life-enhancing resources, such as food supply, housing, economic and social relationships, transportation, education, and health care, whose distribution across populations effectively determines length and quality of life.”

A growing body of research suggests that these resources can have a profound effect on an individual’s health – even the length of their life – and that the unequal distribution of these resources contributes to inequity in the healthcare system.

We at The Foodbank are not experts in public health. However, we do have a responsibility to stay knowledgeable about the way food insecurity intersects with other aspects of people’s wellbeing. In fact, food insecurity is closely linked to health outcomes later in life.

While the terms “food insecurity” and “hunger” are sometimes used interchangeably, “hunger” refers to the physical feeling associated with a lack of food, but food insecurity, defined as the ability to obtain enough food to live a healthy, active lifestyle, is a much more complex issue.

As such, not all people experiencing food insecurity are necessarily starving, and many experience higher-than-average rates of obesity. This may be due to the survival strategy of purchasing cheaper, calorie-dense foods to meet basic dietary needs. Over time, this contributes to issues such as obesity, and heart disease.

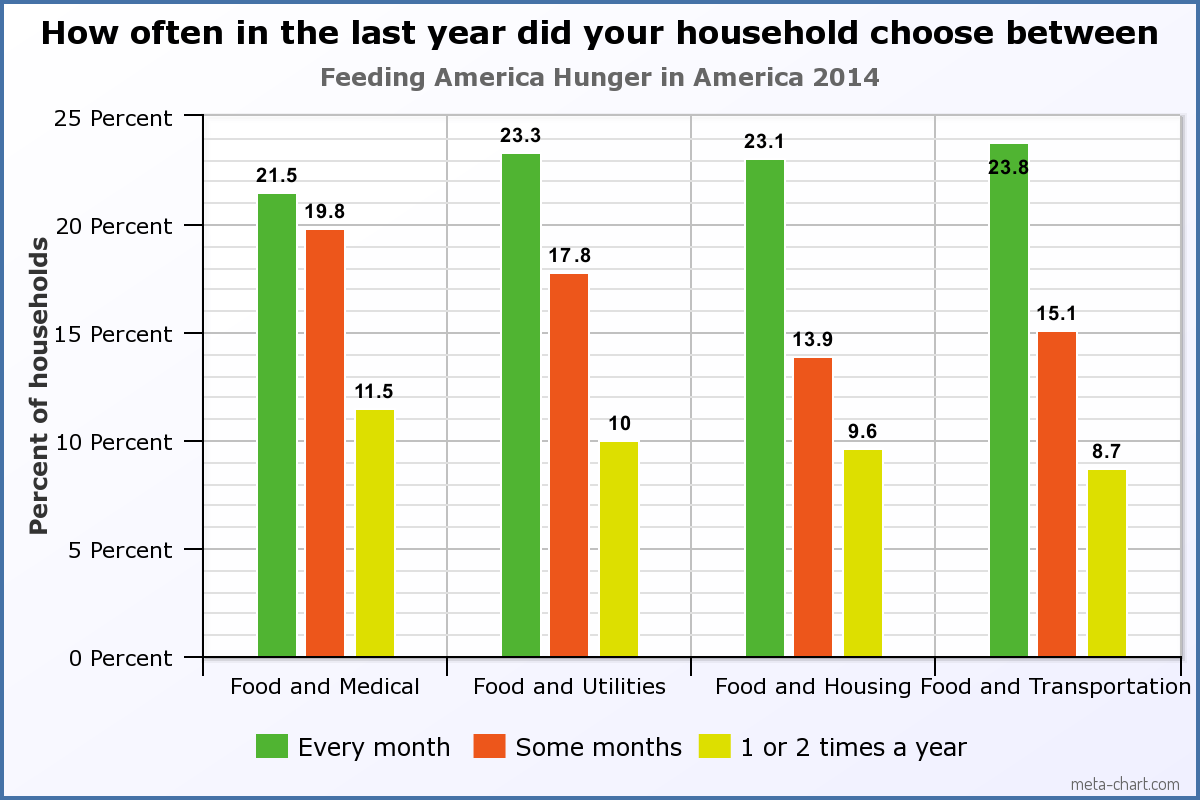

According to Feeding America’s Hunger in America 2014 study, over one in five Feeding America households report having to choose between purchasing food and paying for medical expenses every month

Food insecurity and poor health outcomes also contribute to a cycle of poverty and poor health, which keeps families trapped in patterns that can last generations. Many Feeding America households report having to choose between buying food and paying for medical care. Coping mechanisms such as underusing medications, avoiding preventative care, and failure to adhere to a medically-necessary diet (such as for treatment for diabetes) can lead to higher medical costs and poorer health in the long-term.

As people return to work, concerns of food security are still highly prevalent. Ohio food insecurity rates have doubled due to the coronavirus, jumping from 13.9% to 23%. We saw that same trend here at The Foodbank with visits to our drive thru pantry. About 2,000 families came to visit us in February and 4,684 came in March. Our numbers continued to rise throughout April, finishing out at over 8,000 families.

According to the Dayton Daily News, one in seven Ohioans are still unemployed. Many families are still focusing on trying to pay rent, mortgages, and other bills, leaving little to no room for a food budget. At our June 6 mass distribution in Greene County, we saw 667 families. What is unique about this distribution is that of those families, 521 were new to the food assistance network. This tells us that although many businesses have been able to reopen, people are still seeing emergencies everyday as a result of the pandemic.

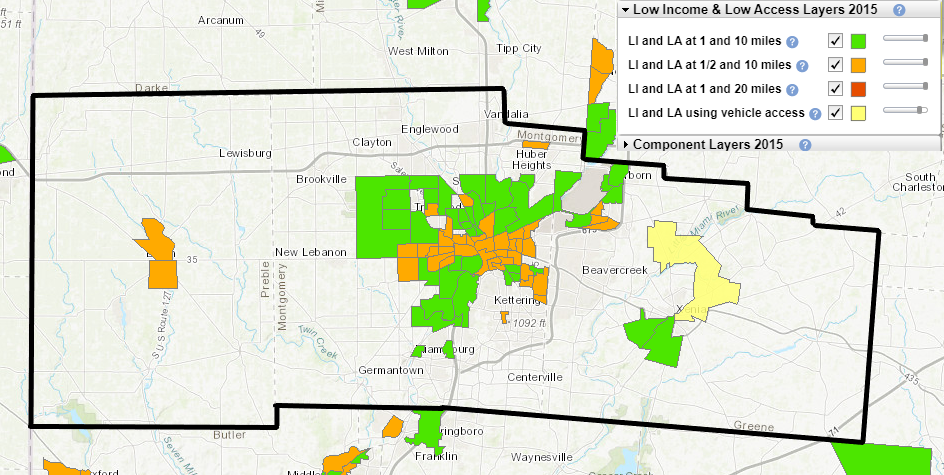

Another often-cited contributor to health outcomes is food access, namely, whether an individual lives in a food desert. An area is defined as a food desert if it is high-poverty with no neighborhood supermarket. (The USDA includes several levels to this definition, which include the percent of individuals with access to transportation, the percent of people living in poverty, and even an area’s rural or urban classification.)

Food access and food insecurity are distinct as food insecurity refers to an individual’s ability to afford food (a function of poverty) whereas food access refers to an individual’s ability to obtain food (a function of environment and geography, which is also a function of poverty). Somebody with low food insecurity may live down the block from a supermarket, but still be unable to afford food, while somebody living in a food desert may be able to afford healthy food, but have no grocery stores nearby.

Living in a food desert is associated with similar health outcomes as food insecurity, including substantially increased risks of obesity and diabetes. Families living in food deserts are often forced to shop at corner markets and convenience stores, which typically offer limited, high-cost, or low-quality selections of fresh produce and protein items.

Food access and food equity go hand-in-hand because areas that are USDA-recognized food deserts are disproportionately communities of color and high-poverty areas. While food access is inherently regional, research from the New York Law School Racial Justice Project has estimated that Black and Latino households are half as likely and one-third as likely to have access to a supermarket, respectively.

A screencap of the USDA’s Food Access Atlas, which shows geographic regions that are low income (LI) and low food access (LA) at varying distances from the supermarket. The Foodbank’s service territory is outlined in black.

In addition to food access issues, food insecurity itself is also racialized. In the United states, 21.2% of Black households, 16.2% of Hispanic households and 10.2% of other/non-hispanic households were food insecure in 2018, compared to 8.1% of white households.

So, what does all of this have to do with COVID-19?

While it may be simple to explain the correlation between race and COVID-19 deaths as due to obesity rates — implicitly blaming victims for overeating — this ignores the reality that many people in high-poverty, predominantly black areas face factors beyond their control that contribute to poor health, such as an inability to afford healthy food or an inability to travel to obtain it.

In fact, a June 10 working paper by MIT researchers found that even after controlling for income level, health insurance coverage, rates of chronic disease such as obesity and diabetes, and public transit usage, counties with higher numbers of Black residents had higher rates of COVID-19 infections.

According to Chris Knittel, the study’s senior author, we have to look beyond these simple explanations to understand why the Black community is facing such a high toll in the COVID-19 crisis.

“The causal mechanism has to be something else,” said Knittel. “If I were a public official, I’d be looking at differences in the quality of insurance, conditions such as chronic stress, and systemic discrimination.”

To see the actions we are taking to promote equitable access to food in our service area, view our impact statement here.

If you’re curious about more of our network data or other social issues such as these, follow us @thefoodbankinc on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Youtube, and Linkedin!

No comment yet, add your voice below!