The long shadow of the “welfare queen” narrative

The majority of public benefits recipients are white, but racist narratives harm benefits access for low-income people of all races.

By Emily Gallion, Grants & Metrics Manager/Advocacy Manager

Some misconceptions about public assistance are easily debunked: Fraud rates in these programs are extremely low, the majority of people who receive assistance are white, and most participants who can work do.

It is more difficult to address the racialization of government benefits discussions. This is because policies such as work requirements that may seem racially neutral first appeared in a much different context.

Many lawmakers made little effort to hide the intent of these policies. Early resistance to public benefits programs included concerns about the economy, which was reliant on low-wage Black laborers.

As one lawmaker said, “I can’t find anyone to iron my shirts!”

In this blog, we will tackle the difficult history of public benefits access for Black households — and how stereotypes about low income people of color have led to policies that are harmful to people of all races.

Demonization of Black Welfare Recipients

Particularly in the South, states added restrictive policies in the 1900s to prevent Black families from accessing aid programs. Some states restricted aid to domestic or agricultural workers, which were predominantly Black. Louisiana limited aid to families during cotton picking season.

As a result, 90% of Black women laborers were initially ineligible for unemployment and Social Security programs, and two thirds were still excluded a decade later, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Some of the worst examples of discrimination in public benefits programs come from the Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) program, created in 1935 to support children living in poverty. This program had origins in mother’s pensions for widows and would later develop into Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

Many restrictions to the ADC originated from racist ideas about Black women, especially Black mothers. Some of these included so-called “man-in-the-house” or “suitable home” policies, which targeted Black and unmarried mothers.

For example, in the three months after Louisiana restricted ADC funding to children whose mothers were “unsuitable” for unmarried sex, 95% of the 6,000 children removed from the program were Black.

Lawmakers expressed particular concern that Black women would have more children solely to increase their benefits. One man, Mississippi State Representative David H. Glass, stated, “The negro woman, because of child welfare assistance, [is] making it a business, in some cases of giving birth to illegitimate children.”

Rep. Glass also introduced a 1958 bill in Mississippi to order sterilizations of women who gave birth to children while receiving benefits. The state of Ohio is one of several to consider similar forced sterilization policies.

The Welfare Queen Myth

These derogatory narratives about Black women appeared more recently in the “welfare queen” hysteria of the 70s. During Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign, he spoke of a “woman from Chicago” who earned $150,000 a year from government checks.

This woman was a real person named Linda Taylor who did receive nearly $9,000 in benefits by using fraudulent names and addresses. Ms. Taylor was a biracial woman with a complicated personal history. Her all-white school expelled her at age 6. At age 14, she gave birth to her first child. Several psychiatrists and lawyers stated that she experienced mental illness and seemed incapable of telling the truth.

This is not to present Ms. Taylor as an innocent victim — some historians also believe she committed a variety of more severe crimes, including kidnapping, child abuse, and even murder. However, she never faced prosecution for any of these suspected crimes. Media coverage of her life focused on her welfare fraud instead.

In total, the county spent $50,000 to convict Ms. Taylor. Her story was amplified to foster the belief that welfare fraud was widespread — in reality, just 1 percent of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare’s annual budget was lost to fraud and abuse, with the majority of ADC mispayments originating from simple mistakes.

A Lasting Legacy

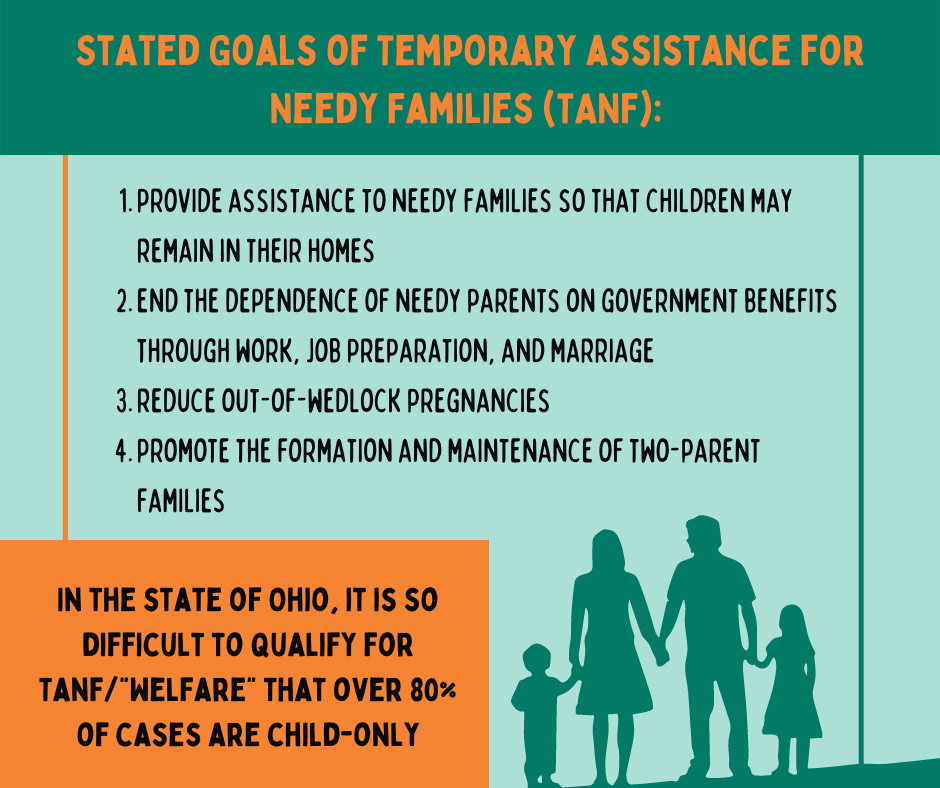

These ideas — that poor people, especially people of color, are lazy, deceitful, and require harsh penalties to coerce them to work — persist in our public benefits system today. TANF, which replaced ADC, still includes language about marriage and unplanned pregnancies that calls to memory the “man-in-the-home” policies of the original program.

Ohio’s TANF program, Ohio Works First (OWF), is difficult for people living in poverty to qualify for. Families can receive OWF for a maximum of three years (lower than the federal standard of five years. To qualify, a family’s gross income can only be 50 percent of the federal poverty level. This is $630/month ($7,560 annually) for a family of three. OWF recipients are subject to strict work requirements with no exception for adults who are ill, pregnant, elderly, or responsible for childcare.

Due in part to these requirements, over 80% of cases in Ohio are child-only, which typically means the child is living with a family member who is not their parent. According to the Center for Community Solutions, Ohio is second in the nation by number of child-only families, behind California but ahead of New York.

While stable, long-term income is a worthwhile goal for people living in poverty, there is little evidence that work requirements in public benefits programming accomplish this. Analysis of multiple studies by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that work requirements ultimately do not reduce poverty — and some families fall into deeper poverty while participating in these programs.

It’s true that work requirements in programs such as TANF and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) do result in modest initial gains in employment. However, these employment increases are not enough to lift families out of poverty. They are also generally not sustained long-term and do not address barriers such as health issues and childcare.

Work requirements disproportionately impact people of color. They are more likely to experience challenges like high local unemployment, transportation barriers, and poor physical and mental health. This, along with alleged bias by caseworkers, may be why people of color are significantly more likely to be sanctioned for work requirements.

Research also shows that people who lose benefits due to work requirements meet conditions that should make them exempt. One study of Tennessee’s TANF funds found around 30 percent of sanctions were made in error.

SNAP also comes with work requirements, which some counties in the state of Ohio are exempt from due to high unemployment rates. These counties are predominantly white and rural, despite that areas with highest rates of unemployment are typically Black and urban.

This is because the state of Ohio administers exemptions at the county level, obscuring pockets of high unemployment within counties. According to analysis by the Center for Community Solutions in 2018, 97% of people living in exempt counties were white.

The same report determined that seven Ohio cities that could qualify for the exemption were home to 40 percent of Ohio’s Black population and over half of Black Ohioans who live in poverty.

Closing Thoughts

It is particularly cruel to characterize people of color as dependent on government assistance when these same programs contain racialized language and policies. While these policies disproportionately impact people of color, efforts to weaken safety net programming harm all people living in poverty.

We support policies that help the people we serve to live a healthy, active lifestyle. We couldn’t do this work without programs like SNAP and TANF. It is our hope that we can implement policies that treat people living in poverty with dignity and respect.

For up-to-date information on policies such as SNAP, you can sign up for advocacy alerts from our partners at the Ohio Association of Foodbanks and Feeding America.

No comment yet, add your voice below!