Planting Seeds of Hope:

Justice for Black Farmers Act

By, Katie O’Donoghue Ly, Director of Strategic Initiatives

The intersection of historical injustice and food insecurity

The challenges Black Americans face today are unique from any other ethnic and racial group. They are deeply rooted in history and supported by data. One needs to look no further than the struggle reflected in food insecurity rates among Black households. In 2021, Feeding America reported that 20% of all Black Americans experience food insecurity. Even more alarming, Black Americans face hunger three times the rate of their White counterparts.

Food insecurity is one of the many harmful consequences of centuries-old systems and practices of exclusion and discrimination. The impact of restrictive land access from this nation’s earliest days created vast disparities and disadvantages experienced by the Black community today. Included among these racial gaps are generational wealth and farmland owned by Black Americans.

The impact of broken promises

The current difficulties of Black farmers can be traced back to unfulfilled promises during the abolition of slavery and the ensuing Reconstruction era. One of the first broken promises followed Union General William T. Sherman’s plan to give newly-freed families “forty acres and a mule” in 1865. Although a mule was never included in the written order, the declaration did provide for the redistribution of 400,000 acres of land. The land had been confiscated from Confederate landowners and transferred to Black families in 40-acre lots. However, President Andrew Jackson overturned the order in less than a year and returned the land to the original White slaveowners. Sherman’s unfulfilled promise had disastrous generational consequences for Black Americans who lost out on land access. The estimated value of the 40 acres that would have belonged to formerly enslaved Black Americans is an astounding $640 billion today.

The contrast between the broken promise of “forty acres and a mule” and the land giveaway known as the Homestead Act of 1862 could not be more significant. The Homestead Act reallocated nearly 270 million acres – 10 percent of all U.S. land – which had been taken from Native Americans and redistributed to 1.6 million White Americans. Unlike the promise of “forty acres and a mule,” there was no immediate repeal of the Homestead Act. More than 150 years later, the effect of the Homestead Act continues to benefit 45 million Americans who reap the generational wealth of that land.

Modern-day disadvantages

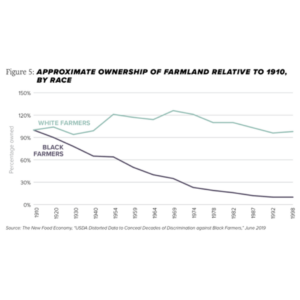

The lack of established wealth and land passed from generation to generation left Black farmers significantly disadvantaged. In 1920, the number of Black farmers peaked at almost 1 million, representing 14 percent of all farmers. Yes, 14 percent was the high point in American history for Black farm ownership. Yet, today, less than 2 percent of all farms in the U.S. belong to a Black landowner, which translates to less than 50,000 Black farmers nationwide. Even more shocking, Black farmers own a meager 0.52% of America’s farmland. The striking contrast in farmland ownership by race is visualized in the graph below.

Compounding historical obstacles for Black farmers are more subtle and modern systems of oppression. Decades-long discriminatory practices by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in denying loans, credit, and land access has nearly eliminated the population of Black farmers. There is a direct connection between discriminatory USDA practices and the enormous land loss among Black farmers. That assertion was affirmed by two successful class action lawsuits brought by Black farmers against the USDA, commonly known as Pigford I (1999) and Pigford II (2010). Both cases demonstrated that the USDA systematically discriminated against Black farmers based on race. Pigford I is one of the largest civil rights settlements in U.S history.

Hope rises

Like a resilient mustard seed growing to fruition, hope rises. Last month, the Justice for Black Farmers Act of 2023 (S. 96) was reintroduced in Congress. The legislation seeks to correct the modern-day historic bias and discrimination against Black farmers within federal farm assistance and lending at the USDA. The law will ensure equality in federal aid, such as loans and debt forgiveness. Additionally, it will enact policies to provide land grants and help protect the remaining Black farmers from losing their land. Other safeguards specified in the legislation include creating an equity commission in the USDA to audit discrimination by the agency against Black farmers and provide recommendations to end the systematic disparities in the treatment of Black farmers.

While it is impossible to undo the harmful effects of centuries-old discriminatory practices, hope offers the opportunity to recreate new systems of equality through action. If done collectively and consistently, visual signs of progress will at last present themselves, such as reducing food insecurity and the racial disparity in food lines.

No comment yet, add your voice below!